For Michel Foucault, those in position of power dominate the production of knowledge; they determine epistemological position. For Edward Said, the discourse in the West on the East has been determined by the West’s position of power over the East. The Subaltern Studies group completed the work of Said and reclaimed their history. They wanted to retake history for the underclasses; the voices of those who had never been heard before, such as peasants, women workers and what Said calls the “other”, but not the elites and the Eurocentric bias of current colonial and imperial history. In the same respect, Said claimed that “every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was. . . a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric.” Ergo, the argument about discourse, power, and knowledge as outlined in Michel Foucault’s work was adopted by Edward Said in his seminal Orientalism. The Subaltern studies group attempts to do work that Said identifies as needed: the retrieval of history lost in hegemonic violence. In this essay, I will discuss the narration of history through Michael Foucault’s lens. Then, I will analyze how Said was influenced by Foucault’s arguments on the relationship between power and knowledge and the concept of discourse. Finally, I will explore how Subaltern Studies group would provide a different narration of history that voices their perspective regarding major historical events—a perspective that has been previously ignored by those in power.

Strong State, Weak Ethnicity and the Rwandan Genocides

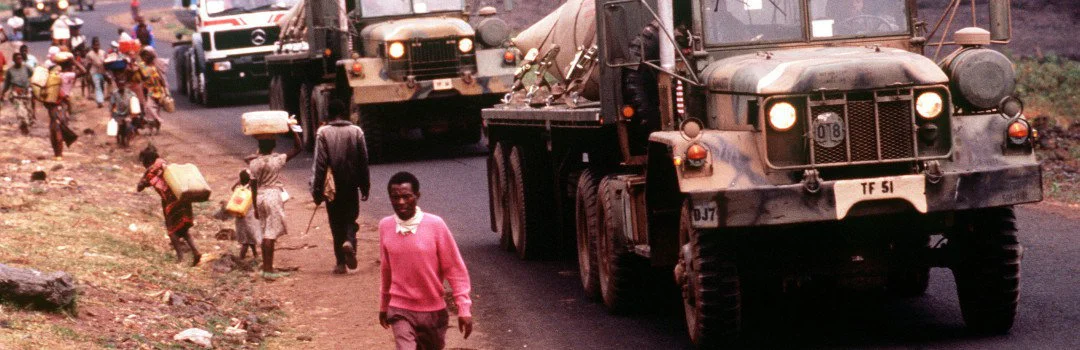

The Rwandan genocide is one of the great human cataclysms of the twentieth century. The genocide was a “systemic and coordinated attempt to physically eliminate the entire Tutsi population of Rwanda.” The most accurate figure for those who were killed in the 1959 genocide, when Hutus seized power and stripped Tutsis of their lands, was 100.00. In 1994, the mortality figures were more immense; 800,000 Rwandese, including moderate Hutu and Tutsi, were killed in the space of 100 days at the hands of Hutu militia and the army. It was the fastest genocide in the history of humanity. This genocide cannot be explained through stereotypes; the actors are far from just “savages”, “barbaric”, mindlessly killing. Although their actions are abhorrent, they are breathing and thinking Homines sapientes who had political motives. How can one explain the Rwandan genocide? Some European commentators had an answer. The trigger that came in 1994 is a product of a deep history. They argue, “African tribes are possessed by ancestral hatreds and periodically slaughter each other because it is in their nature to do so.” In order to deeply grasp the human catastrophe that consumed Rwanda, this paper will analyze the complexity of the contested Rwanda histories of ethnic relationships and the role of a strong state in Rwanda. There are some factors that should be taken into account such as: the pervasive economic crisis, the politicization of both ethnicities, Hutu and Tutsi under the Belgian rule as well as in the independence era in 1959, and the strength of the Rwandan state. I will argue that a strong state, weak ethnicity and the economic situation have led to the Rwanda genocide in 1959 and 1994.

The Genesis of Hezbollah

In the late twentieth century, the Middle East has witnessed a rise of Arab nationalism and a resurgence of Islamic wave that is prominent in both its strength and scope. After being known as “the Switzerland of the Middle East”, Lebanon plunged into the law of the jungle. More specifically, the Islamic movement became the powerful resistance to the existent order, politically and socially that undermine the Lebanese state’s sovereignty. A Shiite movement such as Hezbollah in Lebanon is a clear example of this phenomenon. In the rural region of South Lebanon, 85% of the Shiites were over-represented among the poor working classes. Hezbollah began by the transition from groundwork preparation and being marginalized to not only having an organized institution based on norms and rules but also its members serve in both legislature and the cabinet, while simultaneously maintaining an armed militia. In this paper I will analyze what is particular about Hezbollah and what are the circumstances that made it possible for Hezbollah to become a local, regional and international player in the political arena. I will discuss the historical dynamics of the ‘Party of God’ emergence locally, regionally and internationally and its ideology.

Post-Conflict in Liberia and Crime in Monrovia

Although crime has existed since antiquity, with piracy and slavery, we can no longer assume that a crime committed here and now is an isolated or local incident since we can no longer have this simplicity in today’s complex world. To elaborate, the crime that are seen as local or regional have become relative. The examples of crimes vary widely; they can include drug distribution, homicide, human trafficking and kidnapping. In order to have a critical examination of crimes in post-conflict societies, which is the “no peace, no war” or “neither peace, nor war” situations after the signing of peace accords, it is first essential to understand the nature of conflict. In post-conflict Liberia, there are numerous research topics about Liberia that can be classified under the umbrella of broad categories: civil wars, war crimes and Charles Taylor. One of the main reasons Liberia attracted the attention of the world is because of the atrocities committed during the civil wars. Nevertheless, criminology, as an academic discipline, has not yet strongly emerged in Liberia. What is peculiar and unique in the case of Liberia, in which I will investigate, is the potential in returning the country to war through the involvement of ex-combatants in crime. This makes criminality in post-conflict Liberia a source of serious concern.

Imperialism, Capitalism and Mozambique

In order to grasp the causes of African underdevelopment, one should examine colonial rule in the wider context of European economic power over Africa. In the eighteenth century, the relationships between Europeans and Africans beginning with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade led to the continent’s underdevelopment. Africans were free people until the advent of slavery when they became Africa’s main export. Slave trade refers to the captive and shipment of Africans against their will to numerous parts of the world. They lived and worked as property of the European colonists. In the ninetieth century, the structure and development of the world capitalist system consolidated the underdeveloped structures of Mozambique. The status of Europe and its penetration changed from a source of demand for manpower, particularly slaves, to a source of supply of raw material. Although the colonial rule that began in the early nineteenth century has disappeared since 1975, its impact or outcome has been increasing steadily in Mozambique. In this paper, I will analyze the underdevelopment of Mozambique as a result of colonial rule during the imposition of Cotton Regime (1938-1961). More specifically, what has been the impact of colonialism on the political economy of Mozambique?

Global Environmental Governance & NGOs

There are numerous debates that have been going among international relations scholars over the question of whether non-state actors can be perceived as one of the most crucial actors in international relations and how they can influence states. The realist scholars claim that the state is the most powerful actor in international relations. The neo-liberal institutionalists are in agreement with the realists that the state is the crucial actor, in which the role of international institution should be taken into account in shaping outcomes. For instance, the hegemonic stability theory suggests that a regional order will be achieved only in the presence of a hegemon, whether at a global or regional level, with the capabilities to impose peace. Robert Keohane claims that for “ the creation of international regime, hegemony often plays an important role, even a crucial one.” Kenneth Waltz suggests that the “states are the units whose interactions form the structure of international political systems. They will long remain so.” In this paper, I will answer the question of how the strategies used by non-state actors, rather than the state, particularly non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can impact global governance in climate change. I will take as examples the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conferences that were held in 2009 and 2011.

Islam and Democracy: irreconcilable realities?

The compatibility of Islam and Democracy is an issue that has been recently questioned by today’s society, given the situation in which we are currently immersed. Even though for the last fifty years one hundred countries in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the rest of the world have adopted a democratic model, there are certain countries mainly located in the Middle East and Africa that have failed to join these waves of democratization. These countries happen to have a dominant Muslim population, which is the reason why the compatibility of Islam and democracy is put into question.

Christians in Syria and Egypt

In some Islamic societies, the question of the conditions under which Christians lived remains contested. One of the most strident disputes is the one over the writing of the past about the territories of the Ottoman Empire and how they dealt with the minority groups. In other words, the use of violence against those who were seen as outsiders of the boundaries of the Islamic territories was the endogenously selective memories of former atrocities as well as defeats. There are numerous political activists and statesmen who want to establish Islamic governments in states that are home to non-Muslims. On the one hand, this can provoke fear in the other religious minorities. On the other hand, this can be fervent optimism for others since the Muslims promised the same levels of both justice as well as security for their fellow non-Muslim subjects. This was the case in Egypt and Syria under the same Egyptian rule starting from the 1800s. In this paper, I will answer the following questions: How did the Ottomans sultans deal with the Christians in Egypt and Syria between 1830 and 1860? To elaborate, I will shed light on how the Christians were treated under the same ruler in the 1830-1860 and whether they faced the same destiny or not. I will argue that although the Christians in Egypt and Syria were under the same Ottoman ruler and there was an introduction of modernization policies to achieve equality between Muslims and Christians, there were other factors that made the Christians in Egypt and Syria face different consequences. I will first explain who are al-Dimmis, the positions and situations of the Copts under the rule of Muhammad Ali and the Christians in Syria particularly their massacres of Christians in 1850 in Aleppo and in Damascus in 1860.

A Louder Voice: The Resistance of Women in the Global South

In the post-colonial era, women have often not been considered as subjects of their own histories. Their voices have been silenced between both patriarchal subject formation and imperialist object-constitution. Colonialist elitism and dominant groups dominated the representation of women who live in the developing countries.. For decades, women in the global north often represented women in the global south in racist, imperialist and almost totally ethnocentric ways. Although this representation has been highly influential in the social sciences in reshaping modes of cultural analysis, it has been beset by a number of problems, which are reflected in a growing number of critiques. This paper poses two crucial questions; how in the global north represented women in the global south and which practices exist among women in the global south that counter this representation. I argue that women in the global South have been misrepresented by women in the global North as a homogenous, victimized group, during and after decolonization. Women in the global South have resisted this misrepresentation, arguing and showing in different ways that they were not a single-whole but agents within various unique cultures. This rethinking of the woman of the global South as a subject in fact inspired an updated version of Feminism. Women in the global South have achieved greater agency, which can be seen in their resistance to local power structures.

Greed and Grivance in Sierra Leona

The twentieth century has witnessed a remarkable rise in armed conflicts that are most likely to occur in a weak state as well as a poor country. Furthermore, the rise of “new” non-state actors such as, organized criminal gangs, religious groups, mercenaries, ethnic militias and private security companies are widely recognized. ‘New War’ involves an apparent blurring of the boundaries among struggle for economic and political ends (war) and the force used for private material gain (criminal violence). In the light of the criminal motivations, the civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2002) is an example of a recent complex conflict, amenable to both grievance and greed-based explanation. My position is that, although the violence is in part a reaction to political repression, the drive to possess the country’s valuable resource of diamond explains more convincingly the conflict. In this paper, I will argue that the greed theory is more convincing than the grievance theory in this period of “new wars”.