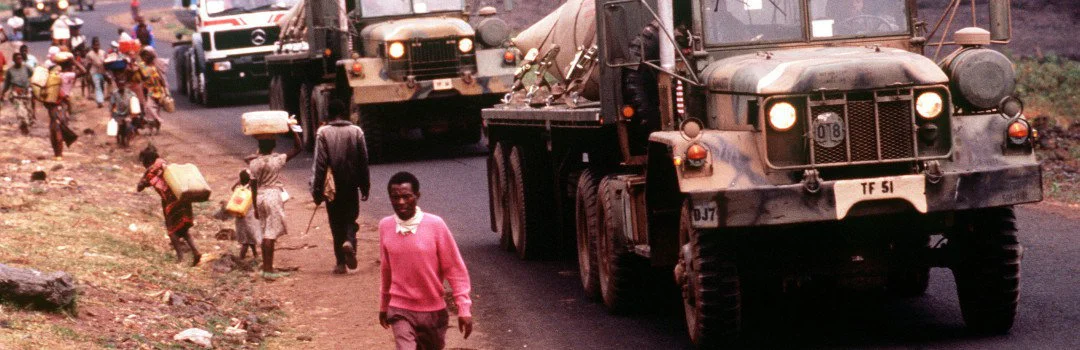

The Rwandan genocide is one of the great human cataclysms of the twentieth century. The genocide was a “systemic and coordinated attempt to physically eliminate the entire Tutsi population of Rwanda.” The most accurate figure for those who were killed in the 1959 genocide, when Hutus seized power and stripped Tutsis of their lands, was 100.00. In 1994, the mortality figures were more immense; 800,000 Rwandese, including moderate Hutu and Tutsi, were killed in the space of 100 days at the hands of Hutu militia and the army. It was the fastest genocide in the history of humanity. This genocide cannot be explained through stereotypes; the actors are far from just “savages”, “barbaric”, mindlessly killing. Although their actions are abhorrent, they are breathing and thinking Homines sapientes who had political motives. How can one explain the Rwandan genocide? Some European commentators had an answer. The trigger that came in 1994 is a product of a deep history. They argue, “African tribes are possessed by ancestral hatreds and periodically slaughter each other because it is in their nature to do so.” In order to deeply grasp the human catastrophe that consumed Rwanda, this paper will analyze the complexity of the contested Rwanda histories of ethnic relationships and the role of a strong state in Rwanda. There are some factors that should be taken into account such as: the pervasive economic crisis, the politicization of both ethnicities, Hutu and Tutsi under the Belgian rule as well as in the independence era in 1959, and the strength of the Rwandan state. I will argue that a strong state, weak ethnicity and the economic situation have led to the Rwanda genocide in 1959 and 1994.

Greed and Grivance in Sierra Leona

The twentieth century has witnessed a remarkable rise in armed conflicts that are most likely to occur in a weak state as well as a poor country. Furthermore, the rise of “new” non-state actors such as, organized criminal gangs, religious groups, mercenaries, ethnic militias and private security companies are widely recognized. ‘New War’ involves an apparent blurring of the boundaries among struggle for economic and political ends (war) and the force used for private material gain (criminal violence). In the light of the criminal motivations, the civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2002) is an example of a recent complex conflict, amenable to both grievance and greed-based explanation. My position is that, although the violence is in part a reaction to political repression, the drive to possess the country’s valuable resource of diamond explains more convincingly the conflict. In this paper, I will argue that the greed theory is more convincing than the grievance theory in this period of “new wars”.